tenements : part 1

Once considered the densest place on earth, New York’s Lower East Side was often the first landing spot for waves of immigrants from many nations. For those arriving from the 1800’s to WWII, the Lower East Side offered opportunities for a new life — access to construction and manufacturing jobs, and economical or cheap housing.

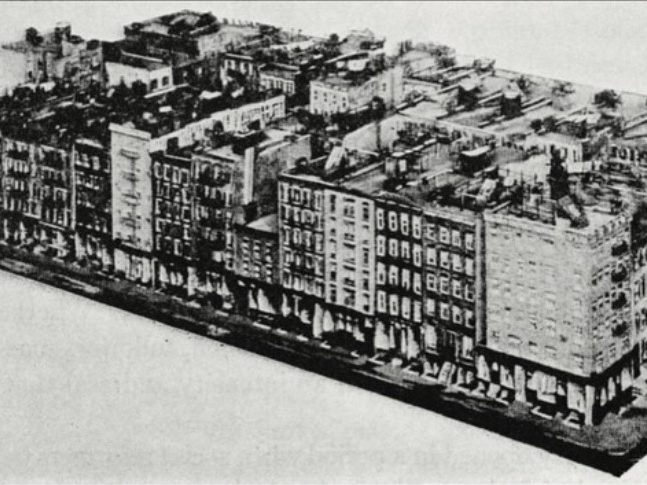

A ‘tenement’ is an apartment building with multiple dwellings — and a shared entry staircase — for rent on each floor. The brick tenement housing typology, with its recognizable fire escapes, made up the fabric of New York’s city blocks and continues to exist to this day.

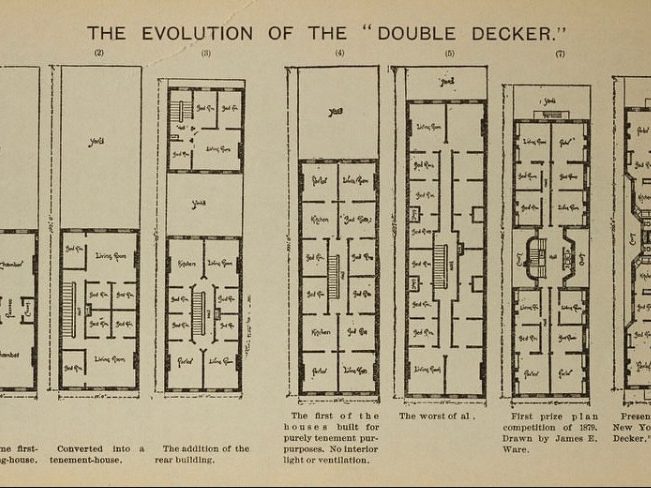

In the early 1800s, lots in the Lower East Side were 25’ x 100’. These lots were owned by individual developers who originally erected one to two-storey wood or brick single-family homes. Due to rapid urban growth and the overwhelming need for housing, the single-family houses eventually evolved into five to six-storey brick tenement buildings. In the 1890s, two-thirds of New Yorkers lived in this type of building.

However, the word ‘tenement’ has negative connotations. The tenements of the Lower East Side and Greater New York, i.e. tenement housing for immigrants and the working poor, were notorious for overcrowding, unsafe and unsanitary conditions, crime, and disease.

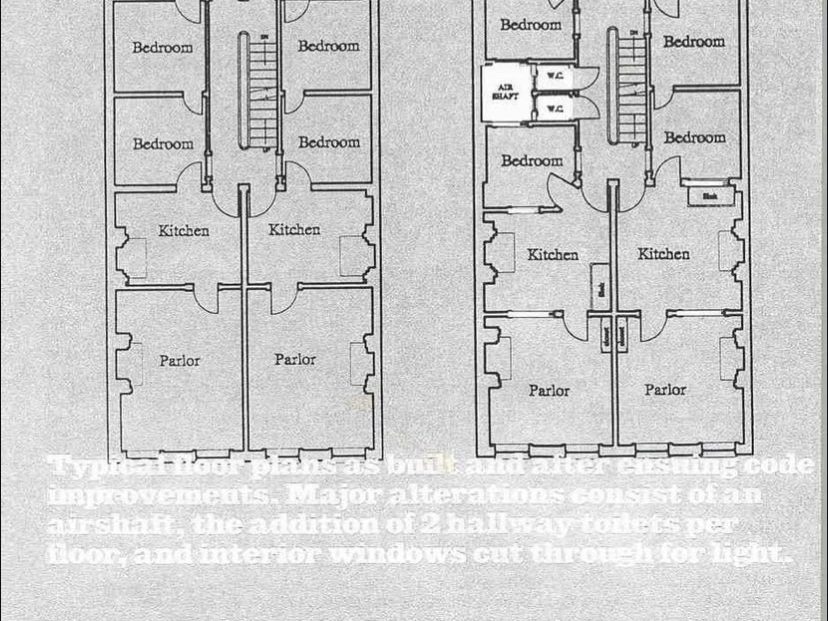

Early tenement housing was built without construction regulation and the living conditions were substandard. The tenement housing lacked light, ventilation, private toilets, running water, gas, electricity, or fire safety elements.

One of the roots of the problem was that early division of 25’ x 100’ building lots — lots originally intended for a single family home — now housed twenty or more families, as well and the occasional tenement factory.

Tenement conditions were eventually recognized as inhumane and reform was deemed necessary, but improvements were slow and incremental.

tenements : part 2

Story-telling museums, museums which share the journey of every-day people, are on the rise.

We visited the Tenement Museum in the Lower East Side and took a tour that explored the lives of two immigrant women who worked in the garment industry, 100 years apart.

Built in 1863, the tenement at 97 Orchard Street housed over seven thousand people until the residential floors closed in 1935, as the landlord did not want to bring the tenement apartments up to building code.

Entering the main hallways of 97 Orchard Street is a visceral experience, like entering a time capsule. The walls, floors, and staircase are layered in history and speak of those who inhabited them in years past.

Early 19th and 20th century immigrants arrived without much money. Most immigrants took jobs in factories with little to no labour laws, where wages were low and job security was unpredictable. Tenement housing was what most could afford.

A tenement apartment usually consisted of three rooms. The front parlour or living room was the only space with access to windows, natural light and ventilation. The kitchen and bedroom were often small, dark, windowless spaces.

Nathalie Gumpertz was a German-Jewish immigrant who lived at 97 Orchard Street in the 1870s. Abandoned by her husband, this single mother supported herself and her four children with a small dressmaking workshop in the front parlour. Business came from word of mouth, and commissions from the tightknit German community.

Women all over the world, particularly women with children or other family responsibilities, have historically turned to live/make spaces to create opportunities for work close to home.

tenements : part 3

In the early 19th century, a growing garment industry helped build New York City. Beginning in the tenements, Jewish and Italian immigrants brought sewing and tailoring experience as they worked from home. The garment and textile industry then evolved with the development of maker districts – with neighborhoods of larger scale manufacturing buildings and commercial and retail spaces.

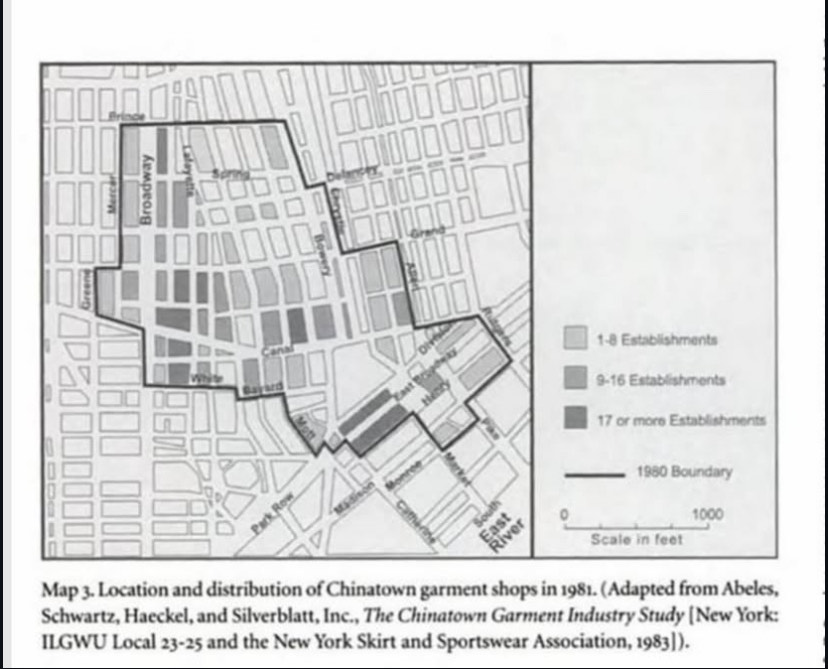

The garment industry in New York reached its height in Chinatown in the 1980s. There were approximately 500 garment factories employing about 20 000 workers, many of them immigrant Chinese women.

Sewing is traditionally considered “women’s work” and perhaps not fully recognized for its creativity and skill. Hours were long, wages were low and working conditions were difficult.

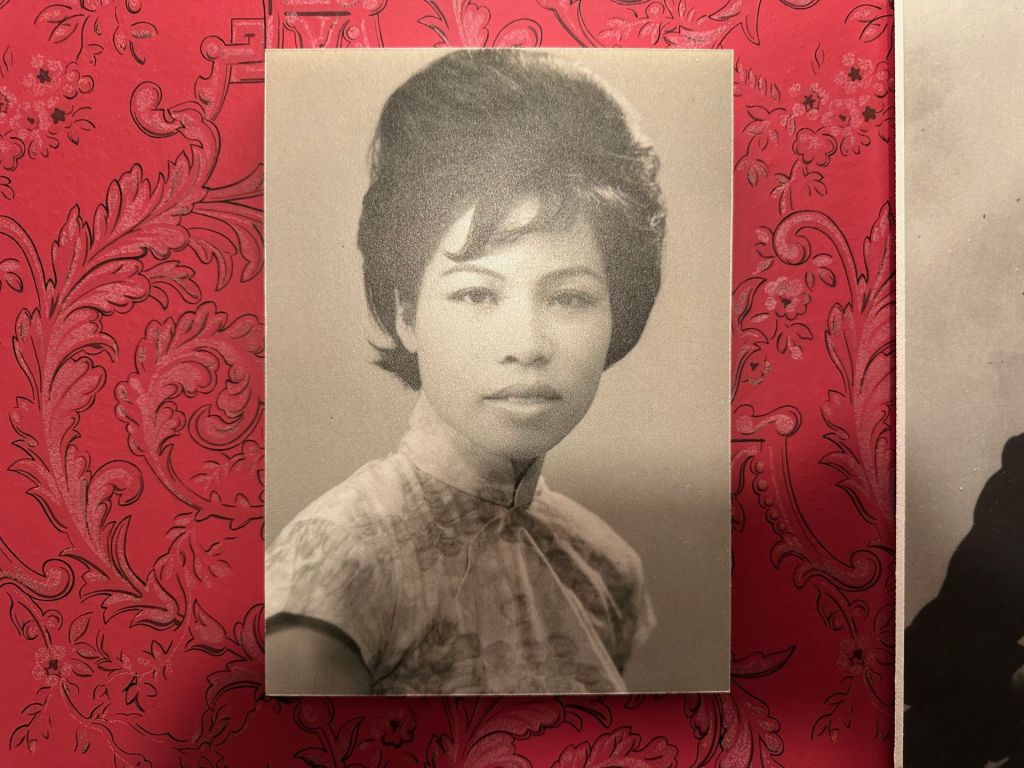

On our Tenement Museum tour, we learned about Mrs. Wong, who moved with her family to 103 Orchard Street in 1968 and worked in the Garment District nearby.

Mrs. Wong speaks about starting with no experience, and working her way up over a thirty-year career to a skilled sample seamstress. She talks about the community of ‘sewing women’ who helped each other navigate life in a new country. Many husbands worked in laundromats and restaurants, with no benefits. These ‘sewing women’ were part of a union — with access to health care, English classes, citizenship classes and social events.

Mrs. Wong speaks with pride about the skills she learned and her contribution to her family. She is pictured, in a dress she made, at each of her childrens’ college graduation.

Large and small-scale garment factories are virtually non-existent in New York’s Chinatown today. In fact, this is true across America. The advent of global outsourcing meant manufacturing jobs in the garment industry went offshore, and never came back.

Gentrification crept in as well. As industries fade, people eventually need visions for the neighbourhoods and buildings left behind. Many former factories all over the world are now adapted into luxury condos or office buildings.