brooklyn : part 1

Cities evolve and are constantly changing. We wanted to see examples of the current state of manufacturing in New York and spent a busy and informative day in Brooklyn with Andrew from Turnstile Tours.

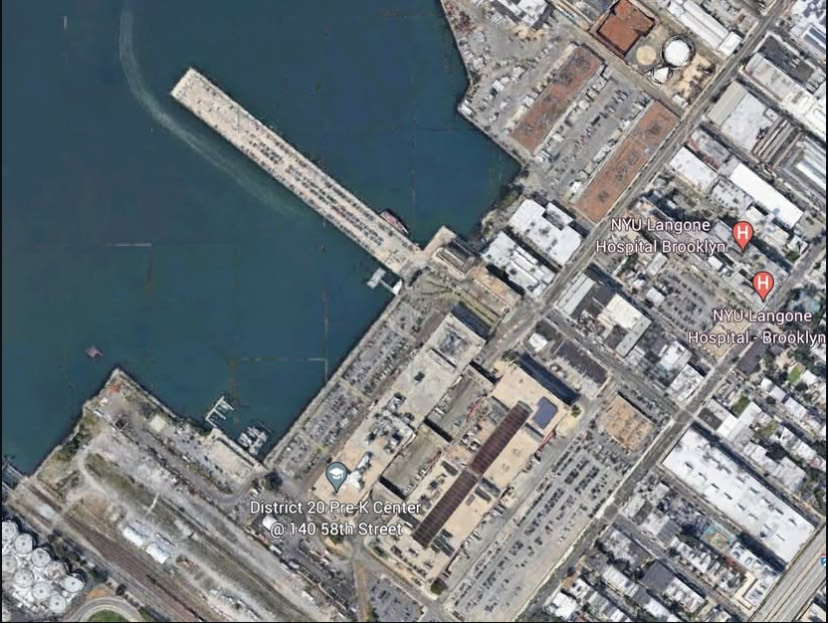

The Brooklyn Navy Yard (BNY) and the Brooklyn Army Terminal (BAT) are located on the western shores of Brooklyn, across the East River from Manhattan.

Both large complexes were originally built for the US military. The Brooklyn Navy Yard’s main purpose was ship building and ship maintenance. The Brooklyn Army Terminal was constructed for warehouse storage and logistics.

The Brooklyn Navy Yard and the Brooklyn Army Terminal reached their functioning heights during WWII, and were both decommissioned in 1967. They were subsequently bought by the City of New York, with the intention of converting the mega properties into urban industrial parks. This was an attempt to preserve manufacturing spaces in Greater New York by offering relatively affordable and stable rent.

There is no live component to the Brooklyn Navy Yard or Brooklyn Army Terminal. We understand that if the industrial zoning in this area were changed to allow residential development, it would set a dangerous precedent. This would make it difficult to preserve manufacturing use, as residential real estate values would overtake the land.

However, the Brooklyn Navy Yard and the Brooklyn Army Terminal are very much worth studying as contemporary, urban industrial hubs. The next parts will look at their history and current use. We will assess their siting, relationship to the city and street, access to transit, size and scale, and sense of community — both inside the properties and within the surrounding neighborhood.

brooklyn navy yard : part 2

The Brooklyn Navy Yard (BNY) s a storied, naval shipbuilding facility. This site covers approximately 300 acres and contains dozens of structures, some from the 19th century, some more modern.

This Navy Yard, a small city within the city, includes six dry docks, a power plant, a radio station, a hospital, railway spurs, machine shops and storage warehouses. Over the decades, it employed thousands of skilled workers from New York, Brooklyn, and beyond.

BNY is well recognized for its revitalization strategies concerning industrial sites, as well as the preservation of manufacturing work space and jobs. When the US Navy left and the City of New York took over, it was very difficult to find a sole tenant to take over such an expansive space. Like many industrial sites all over the world, the Brooklyn Navy Yard was simply too large.

After some experimentation, blocks and buildings were broken up into smaller units, and then smaller still. This variation in sizing allows them to provide rental space for a small start-up, a mid-size and a larger business — degrees of growth all within the same complex.

In the Brooklyn Navy Yard Museum we saw an exhibition which showed the yard’s historical use, as well as photographs of its current, diverse mix of tenants. There are traditional manufacturing companies, focused on furniture, woodworking, metal working and welding. There are food producers, small artisan makers and more established companies. In addition to the makers, the ferry maintenance, and the repair docks, this sprawling complex houses a film studio, a military sewing gear company, a commercial farm, a company experimenting with technology for a self-driving car, and a STEAM school. There are also partnerships with New York educational institutions and sustainable development initiatives.

There is no doubt this is a creative industrial hub, but the Brooklyn Navy Yard was a purpose-built secure facility and it differs greatly from our understanding of maker districts and how they integrate and transform neighborhoods.

brooklyn navy yard : part 3

It is perhaps unfair to assess the Brooklyn Navy Yard and its integration with the surrounding city through the lens of a maker district.

The Brooklyn Navy Yard was a purpose-built facility for the US Navy. Bordered by the East River to the North and multiple city blocks to the South, this secure compound was never meant to welcome the city. To this day, it is separated from close-by neighbours by a fence and gated with few points of entry.

The Brooklyn Navy Yard successfully adapts and re-uses its 19th century industrial workshops, post-WWII utilitarian administrative offices, and storage warehouses. It has preserved work space for a diverse mix of small makers and large manufacturers, and it has given opportunities for entrepreneurs and established companies to form communities.

Where the Brooklyn Navy Yard might falter, is in its relationship to the city. The siting is ideal for shipbuilding but it is less than ideal for a busy creative hub, as there is no easy or quick access to transit to New York and its surrounding boroughs. There is a ferry stop and several bus routes, but there is no subway stop within walking distance.

The roadways inside this sprawling industrial complex are private, not city streets. Furthermore, these roadways are empty — the military never planned to develop workshops in conjunction with retail, consistent pedestrian traffic, or lively streets.

Hallways and elevators in a vertical city can never encourage or replace the spontaneous interactions of a street. Many of the ventures in the Brooklyn Navy Yard rely on online shops or other means of distribution. Visits to showrooms operate very differently from those located in a neighborhood block. Access is not drop-in, but by appointment only.

brooklyn army terminal part : 4

press for video

The Brooklyn Army Terminal (BAT) was a purpose-built logistics and warehouse facility. Built around WWI, reaching its height of productivity in WWII, this 100-acre complex consisted of two warehouses, three piers, administrative buildings and a train storage yard. Originally used as a US Army supply base, the BAT was sited in the midst of roadways, seaways and railway lines that connected to all parts of the USA.

At the time of construction, the two eight-storey concrete warehouses were considered the largest concrete structures in the world. Railroad tracks still run through Warehouse B’s light-filled central atrium. The loading balconies are staggered diagonally, while a moveable overhead crane once transported cargo between the train and balconies.

Parts of Building A and B were adapted and re-used by the City of New York to preserve light manufacturing space. The structure of the concrete columns allow flexibility to partition the floors into smaller units. Several phases have been renovated and are in use but the BAT still feels a bit empty. These buildings are massive and the renovation costs to introduce basic amenities must be staggering.

The Brooklyn Army Terminal is a much needed creative industrial hub. But when viewed through our definition of maker district, the Army Terminal also falters in its relationship to the city. There is a ferry stop, but New York seems very far away. The siting amidst road, rail and water works well for a supply base, but as a maker district, the experience is the opposite of welcoming. Current visitors and tenants have to navigate through a network of roadways filled with industrial warehouses, loading docks and tractor trailers. There are occasional public events, but the BAT could handle thousands of visitors and this complex would still not feel crowded.

The next part will look at some of the workshops and makers in the Brooklyn Army Terminal — one with perhaps the largest square footage, one with perhaps the smallest.

brooklyn army terminal (MakerSpace NYC) : part 5

Many years ago, we had more exposure to making at a young age. High school curriculums offered home economics, woodworking, and machine shop. Those days are long past. Many rooms have been re-purposed, the tools and equipment sold off, the teachers transferred or retired, and a broad base of knowledge lost.

However, across the globe, there is a rise in micro-businesses, small batch production and maker spaces. Much has been written about the hands-on approach to learning, and communal workshops provide makers with a place to come together to design, experiment, build and create. The high school shop class has been re-branded, and some version of maker spaces can now be found in private ventures and public institutions such as schools, libraries and museums.

MakerSpace NYC, located in the Brooklyn Army Terminal, is one of New York’s largest maker spaces. We spoke with Scott about how difficult it is to find affordable fabrication space if you are a small-scale maker and entrepreneur, and heard stories about the years long journey to form MakerSpace.

MakerSpace operates like many other communal workshops, offering memberships and day passes. The equipment and tools can be traditional — woodworking tools, welding equipment, sewing machines, tech-heavy 3D printers, CNC machines and water jet cutters — or low tech, with hand tools, arts and crafts supplies or lego.

MakerSpace operates like many other communal workshops, offering memberships and day passes. The equipment and tools can be traditional — woodworking tools, welding equipment, sewing machines, tech-heavy 3D printers, CNC machines and water jet cutters — or low tech, with hand tools, arts and crafts supplies or lego.

MakerSpace is a non-profit organization. They are representative of a new generation of workshops that aim to use industrial and digital fabrication equipment to benefit the community. There are partnerships with schools for field trips, afterschool programs and summer camps, as well as many events to welcome and build the maker community. There is kinship and common ground to be found, especially when beginners learning new skills coexist beside experienced makers — those who might be working through a project or prototyping a design.

brooklyn army terminal (purgatory pie press) : part 6

press for video

Small-scale makers, artisans and entrepreneurs used to be found in many different neighborhoods, in many different cities. They bring creativity, enthusiasm and energy to a space, contributing to diverse and vibrant communities. But in these hard economic times, small-scale makers and manufacturers are being squeezed out of both housing and affordable workshop spaces.

In a small, inspiring, light-filled studio we met Dikko and Esther of Purgatory Pie Press.

Specializing in letterpress printing and book arts, Dikko and Esther have collaborated on limited editions, artist books, cards and prints. Their activities are widespread and varied — they teach, lecture and exhibit, participate in maker fairs and pop-ups, and in general promote experimenting with traditional letterpress techniques for a contemporary practice. Within a career spanning forty years, works by Purgatory Pie Press have been included in exhibitions at the Met and the Victoria & Albert.

For almost thirty years Purgatory Pie Press was located in Tribeca. Their needs were always small, less than 600 square ft. However, many years of rising rent contributed to the decision to move out of New York City and into the Brooklyn Army Terminal. Artbuilt offered a choice of units with a small square footage, relatively affordable rent, and the important stability of a predictable long-term lease.

When moving to new neighbourhoods, artists, artisans and small-scale makers often gravitate towards each other, finding or building like-minded communities. But what happens to the streets, neighbourhoods and pockets of culture in the cities they have left behind?