Since the Middle Ages, Ghent had prospered due to the textile industry. The manufacturing of cloth and its resulting trade was supported by many small urban workshops.

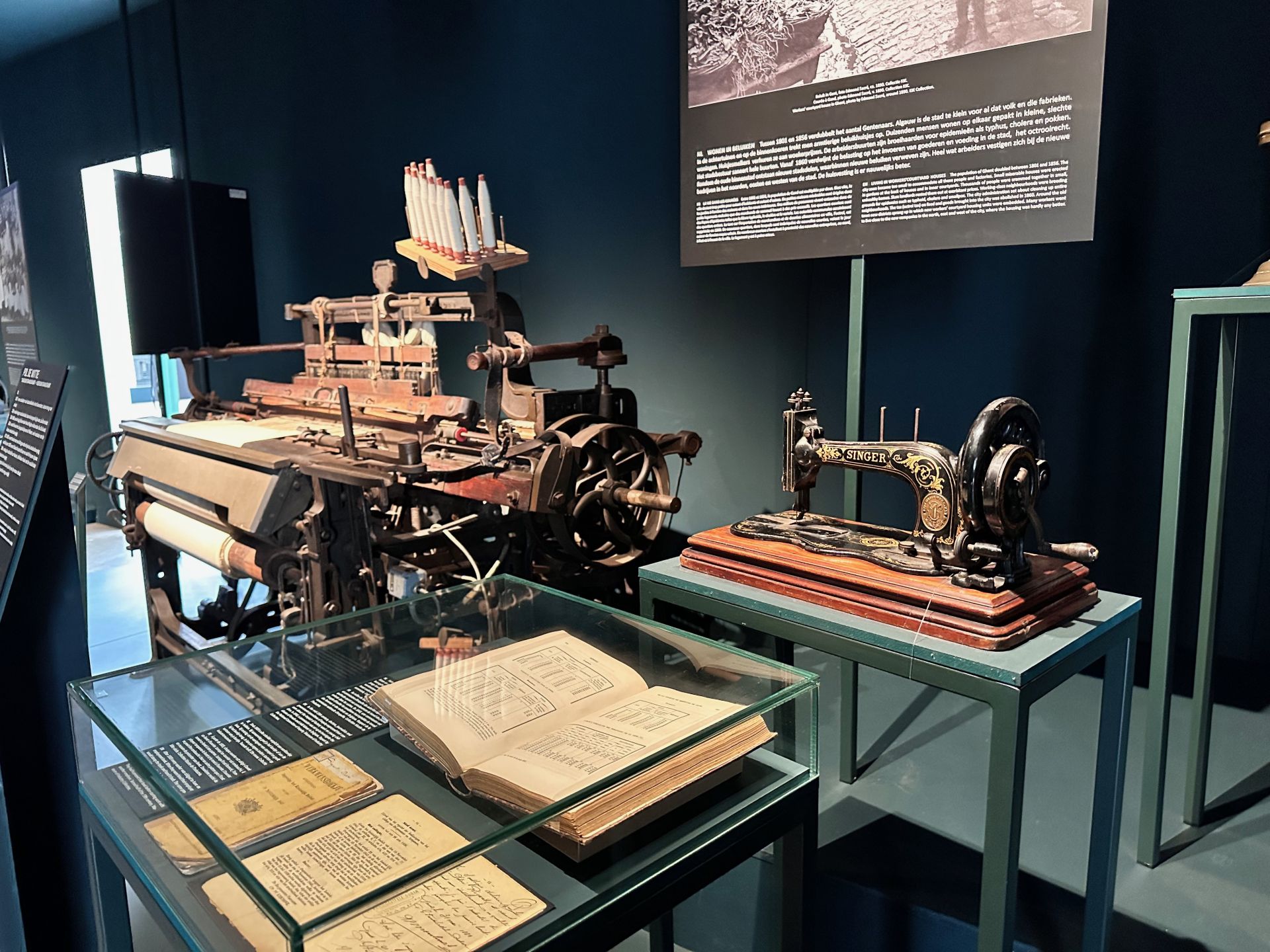

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Ghent’s textile industry underwent industrialization, with the introduction of mechanical innovations such as the Mule Jenny (a large spinning machine) and the mechanized twiner.

By the end of the 19th century, Ghent was considered the center of Belgium’s industrial belt. Ghent had 1500 textile factories of varying sizes scattered throughout its townscape. There were also industrial bakeries, copper foundries and other heavy industries. And Ghent’s population had tripled, with people from rural areas looking for work and immigrants from North Africa and Turkey.

Tenement housing or beluik sprung up beside the factories. These small, dark, cheaply and shoddily built homes were arranged around a courtyard and reached through a narrow alley off the street.

With similarities to the nagaya in Japan, these beluik, or working class tenements, were overcrowded, lacking adequate water and sanitary facilities, and prone to disease and epidemics.

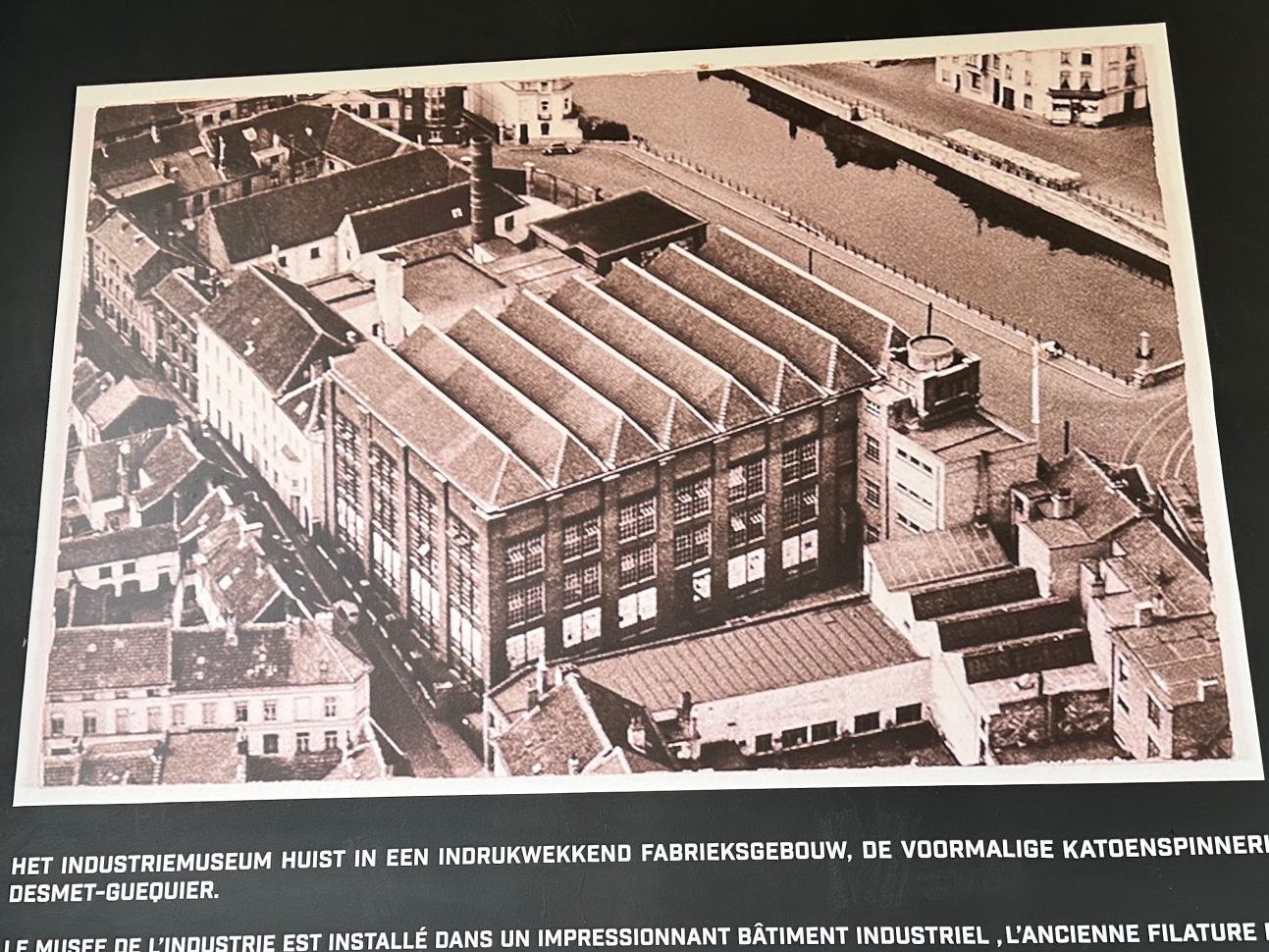

Small and large factories, and a dense worker housing network formed the urban fabric in many parts of Ghent. When the multiple industries declined, factories, warehouses, workshops, worker housing and courtyards were left behind.

From the air to the soil, you can find remnants of Ghent’s industrial past — smokestacks, warehouses with sawtooth roofs, and open courtyards.

While many are abandoned and in disrepair, a few of these industrial spaces are now being given a chance at a second life.