Throughout history and across many countries and cultures, people have lived where they worked. Examples of combined domestic workplaces are varied and plentiful, including schools, churches, restaurants and shop houses. Post-Industrial Revolution, most live/work and live/make models were discouraged. Urban planners enacted policies to separate live and work, rightly citing issues related to congestion, noise, air pollution and unsanitary conditions. During this time, working from home and living at work was often illegal.

We live in Toronto. Our streets and neighbourhoods look very different from those in Japan, and much of that comes down to urban planning.

Most of North America uses a zoning where streets and blocks are separated into residential, commercial or industrial. There was and is a concerted effort to create laws and by-laws of similarities.

Industrial zones and manufacturing districts do not have residences. Years ago, there used to be many local convenience stores and coffee shops deep in residential neighbourhoods. Now, it is rare to see a new, small-scale non-residential building (work or make) in a residential area.

In North America zoning is set at the municipal level, while planning departments manage individual projects on a case-by-case basis. If you want something different, it takes a long time and a substantial amount of paperwork for the planning department to review, approve and issue a permit. There is no guarantee of approval.

Across the world, micro-businesses, small-batch production and maker spaces are on the rise. Meanwhile, progressive urban planners are experimenting with various types of live/work zoning for small businesses and small-scale makers.

north american zoning vs japanese “inclusive” zoning : part 2

We think of Japan as a country of tall buildings, and while in many ways it is, it also isn’t. Japanese cities have concentrated density at their financial centers, commercial shopping districts and major transit hubs. But a significant percentage of area in Japanese cities and towns are comprised of 2-storey or low-rise residential.

Exploring residential neighbourhoods, we often see the unexpected : mixed use, mixed scales and mixed forms. What is considered unusual for North America is perhaps usual for Japan, as non-residential and residential uses are allowed to co-exist.

Cities change and evolve. Some of these buildings and their usage have been there for decades, predating their neighbours. Some businesses have taken over existing buildings and changed usage. Some buildings and businesses are new.

Japan’s “inclusive” zoning creates space for makers and maker spaces which are not located on any main commercial street or in any primarily industrial districts. These small-scale, non-residential buildings might be situated in a residential block and stand beside residences or other non-residential properties.

north american zoning vs japanese “inclusive” zoning : part 3

Japan’s zoning and approach to mixed-use buildings is different from that of other developed countries. From the Edo period, Japan’s town planning and land use was based on a strict social order and hierarchy. In this time before modern zoning regulations, neighbourhoods were often formed around similar makers (i.e. pottery, textile, leather making) and their surrounding ecosystems of supporting industries, suppliers and shops.

The individual machiya, with a combined dwelling and work space, formed the building blocks for the streets. It was common for the merchant shop houses to be side by side with the artisan workshops.

Takayama is one of the best preserved towns from feudal times, showing a series of streets of machiya.

The co-existence of live and work was once considered the norm in Japan. The concept of an intertwined residence and workplace is so strong that it is carried forward and reflected in modern-day Japanese “inclusive” zoning.

japanese “inclusive” zoning : part 4

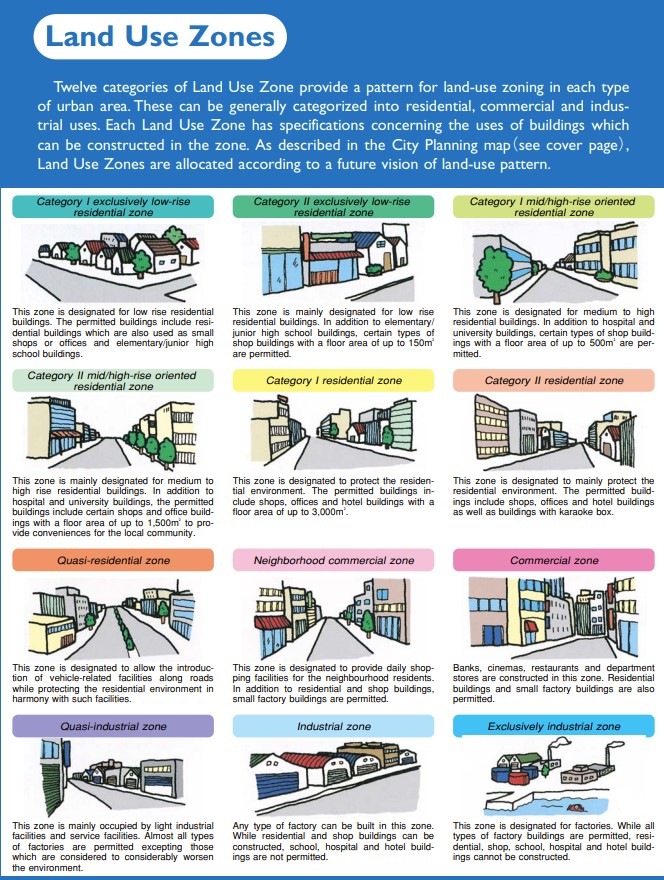

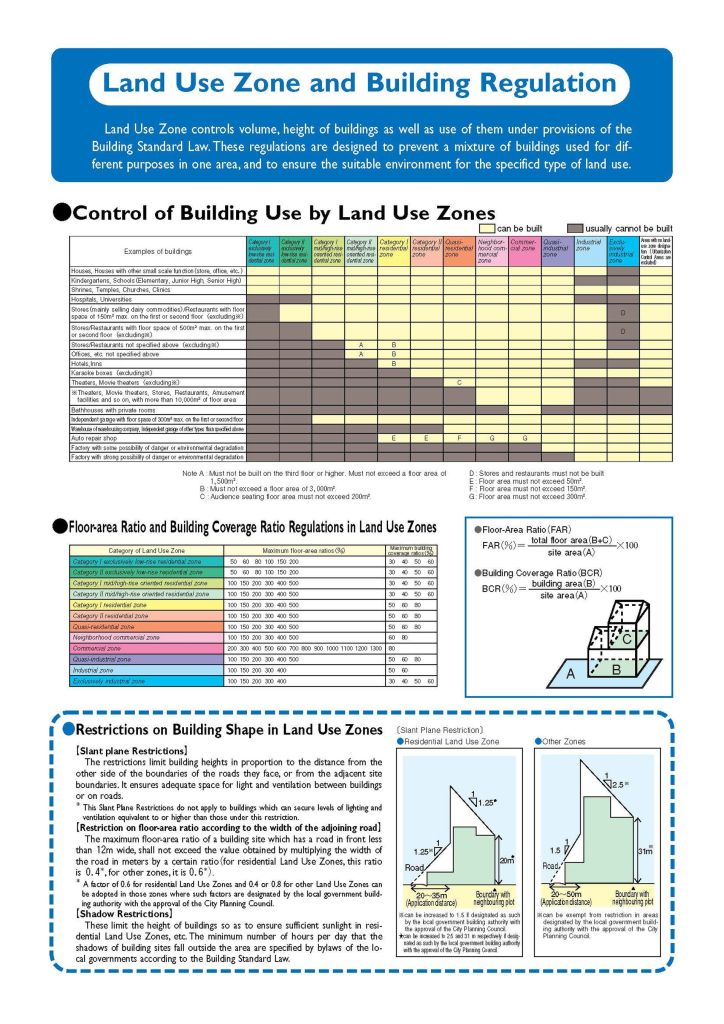

Japan has hardly any areas with only one type of designated land use — purely residential or purely commercial. Rather, Japan’s zoning by-laws are national and considered “inclusive.” This “inclusive” zoning restricts “heavy industry,” but allows most other development.

To put a complex issue in simple terms, land use in Japan is designated into 12 zones. 11 out of the 12 zones allow residential, and are essentially mixed-use. The result is that you will see a diverse mix of use and scale on a Japanese street and block : single family dwellings, multi-family high rises, and a wide variety of small businesses and small-scale makers.

Bouldering Granny (Tokyo) is a tiny bouldering gym, set between residential highrises instead of an industrial park. It is accessible by transit and walking, not by highway.

Coconotane (Kyoto) is an artisan bakery located on a residential street. This venture replaced an existing carport and has been welcomed to the neighbourhood.

The fabric of Tokyo, as well as many parts of Japan, is made up of thousands of small businesses and small-scale makers.

There are more opportunities for the smallest of entrepreneurs to envision and set up a business, all with relatively minimal start-up costs. This is because :

1) “inclusive” zoning allows mixed-use as a right, with less paperwork for approvals

2) the wide, potential availability of non-residential use in a residential area means that you are not restricted to locations on main commercial streets with higher rents

3) the Japanese have learned to accept and optimize a compact footprint